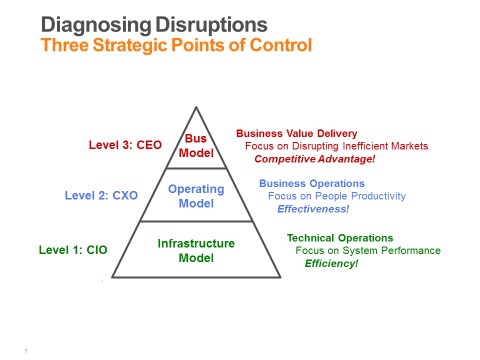

You’d have to be Rip Van Winkle not to know by now that software is eating the world and digital is disrupting everything, including you. But knowing exactly how you are getting disrupted and exactly what you should do to respond are not always so obvious. In such cases, here is a framework that can help you get a better bead on things pretty quickly:

The claim of this model is that digital disruption can strike at any one of these three levels, with escalating impact as you move up the triangle. Regardless of whether you are the disruptor or the disrupted, you need to know which levels are in play in your specific case.

The claim of this model is that digital disruption can strike at any one of these three levels, with escalating impact as you move up the triangle. Regardless of whether you are the disruptor or the disrupted, you need to know which levels are in play in your specific case.

Level 1 disruption applies to technologies and business models that disrupt the customer’s IT infrastructure but do not impact their processes outside of IT. Cloud computing is a good example of this, as is the XaaS business model that provides software, platforms, or infrastructure as a service. These have dramatically changed the economics of IT itself, enabling much smaller companies to acquire much more sophisticated IT services at much lower cost than ever before. If all the customer wants to do is capture these economics directly to improve the price/performance of IT, transfer risk liability to the vendor, and reduce the total cost of ownership, then the entire transaction can be managed by and contained within the IT organization. The customer’s operating model will not change, nor will its business model.

From an IT vendor’s point of view, a Level 1 transaction has both pluses and minuses. The big plus is that IT already has both the authority and the budget to do the deal. The bad news is that this is a cost reduction play that will entail deep discounting to close the sale. The vendor can get a few points of margin for risk-reducing services, but that is about it. This plays into the hands of commodity vendors more than category leaders who forego the advanced R&D and upscale marketing in order to support a lower cost structure. It is a transactional game where brand counts for little and loyalty counts for less. But it does move a lot of gear, and does so fairly quickly.

Level 2 disruptions are quite a different case. Here the customer’s primary objective is not to upgrade their IT infrastructure but rather to modernize their operating model. To be sure, to achieve this objective they will have to upgrade their IT—indeed, the technology disruption in IT is what is making it possible to modernize their operating model—but IT is not the point. The new operating model is the point. That means not only new technology but also new systems, new processes, new roles, and new key performance indicators. Think of how retailers are trying to change the in-store operating model to compete better with online alternatives. Think of how banks are trying to migrate from neighborhood branches to online self-service and mobile apps. Think of how airlines are migrating from check-in counters to kiosks and from kiosks to their own mobile apps. Next-generation IT can have a huge impact by delivering superior customer service at a fraction of the cost. But there is also a much larger change management journey that must be navigated in order to secure these gains. Such changes cannot be sponsored by the IT side of the house. They fall within the line of business executive’s purview.

From an IT vendor’s point of view, again, there are pluses and minuses here as well. The big plus is that there is much more budget in play here that can result in much bigger deals. Moreover, the customer is less price-sensitive because they are more risk-sensitive. Changing out your operating model is like open heart surgery—you are not looking for the discount offer. Instead the customer seeks out one or more trusted advisors, people backed by companies who have the knowledge, the reputation, and the resources to put a safety net underneath the effort. In particular, they are looking for a single vendor who can meld advanced technology capabilities with domain-specific operating model expertise. This is typically either the lead application software vendor or the lead systems integrator. When a vendor can secure this position, they find themselves on the same side of the table as the customer, and a very strong and profitable relationship can develop.

The big challenge of Level 2 deals is that the vendor has to help create budget before they can compete to consume it. This means identifying and then engaging with the line of business executive sponsor who may or may not have any interest in talking with an IT company. It means having a deep enough understanding of the dynamics of the customer’s industry and operating model to understand the economics of the project and target the process steps that will generate the highest returns. This is sophisticated stuff. There are a handful of people who are truly gifted at it, but not more than that. In order to scale Level 2 strategies, therefore, vendors have to target and commit to specific vertical markets where whole segments of customers are all in some stage of a sector-wide operating model shift. This, in turn, requires the vendor to refocus their own product marketing, marketing communications, sales coverage, and the like.

Finally, to close a Level 2 deal you have to herd a lot of cats. Worse, some of these cats may not like or trust each other, and even the best orchestrated deal can sometimes run off the tracks. For these reasons it is critical that these deals be priced high enough to warrant the risks they entail. If low price ends up winning at the end, that signals a failure in the deal process all around, as no one is going to be happy with the final result.

Level 2 deals are the bedrock of all major enterprise IT franchises. That said, they are not the biggest nor the most glamorous. That title goes to the Level 3 deals. Here the disruptive customer’s strategic intent is to upend an entire industry by introducing a novel business model along the lines of what Uber is doing to transportation, Airbnb to hoteling, and Amazon to retailing. In response some disrupted customers may try to follow suit, but this is not normally a good strategy as there is just too much inertia to move in their customer and partner ecosystems. This is why Barnes & Noble has struggled with e-readers, for example, or why Kodak could never get anywhere with digital photography, even though they invented it. Level 3 disruption is basically a game you want to play on offense, not defense. This does not rule out established franchises from playing. The only rule is, do not try to disrupt yourself. Always play to disrupt someone else.

The Level 3 executive sponsor has to be the CEO, or the moral equivalent in a holding company enterprise. This is a bet-the-business kind of play with huge upside potential offset by the equal likelihood of a smoking crater. It attracts early adopting visionary leaders who want first-mover advantage in catching the next big wave and riding it to glory. They tend to be charismatic evangelists who can inspire high-risk, high-reward investors to back their play. They are looking for vendors who have breakthrough technology and/or the systems integration chops to build first-of-their-kind systems on top of yet-to-be-proven-out protocols and standards. It is a project business end to end, producing a single bespoke solution that the customer wants exclusive rights to for the foreseeable future. We have seen this is media with Google and Facebook, automotive with Tesla, and in biotech and pharmaceuticals with Genentech and its progeny. All broke radically new ground, and all exploited disruptive technology to do so.

From a technology vendor’s point of view, it’s another balance sheet of pluses and minuses, with both being super-sized. On the plus side, these projects put next-generation technologies on the map. A single big success can tee up an entire franchise for a decade or more, first by making everyone aware of the new capability, then by tagging the winning vendor as the de facto standard and the safe buy. This attracts both customers and partners, and if the project can be template enough to become a repeatable solution, it will generate an ecosystem of interested parties that will further cement the lead vendor’s top-dog status. Also, just as pragmatists are not price-sensitive when it comes to selecting heart surgeons, visionaries are not price-sensitive when it comes to funding the Next Big Thing. They want their vendors to have plenty of money to work with because they know that what they are trying to do has never been done before and will need more than one rescue operating to get to the finish line. So Level 3 deals can be big—indeed, very big!

On the downside, Level 3 projects are exceptionally hard to sell and even harder to fulfill. Multiple executives in the vendor organization have to build deep personal relationships of trust with their executive counterparts on the customer side. Executive briefings are legion. Resource commitments are deep. Design engineering is contributed for free as part of the marketing effort. Product road maps get torn to shreds. Systems get overridden. Organizations get overthrown. Predictability is close to zero. If successful, revenue linearity now looks like a python that has swallowed an elephant. Bottom line: when there is this amount of disruption, no matter how much money is paid out, it will not cover the costs. There is only one rule in this kind of game, the one the former owner of the Oakland Raiders is famous for articulating: Just win, baby!

So as you take stock of your current circumstances, whether as a customer or as a vendor, be clear with yourself as to the kind of disruption you are dealing with, and make sure you are bringing the right team to the table and setting the right expectations for closure. Digital disruption can pay high dividends to us all if we play these games right and extract high penalties if we play them wrong. No need for mistakes here, and no room for them either.

That’s what I think. What do you think?

Source : Geoffrey Moore (Author, Speaker, Advisor)